An Analysis of William Shakespeare's ROMEO AND JULIET

This story of star-crossed lovers is one of William Shakespeare’s tenderest dramas. Shakespeare is sympathetic toward Romeo and Juliet, and in attributing their tragedy to fate, rather than to a flaw in their characters, he raises them to heights near perfection, as well as running the risk of creating pathos, not tragedy. They are both sincere, kind, brave, loyal, virtuous, and desperately in love, and their tragedy is greater because of their innocence. The feud between the lovers’ families represents the fate that Romeo and Juliet are powerless to overcome. The lines capture in poetry the youthful and simple passion that characterizes the play. One of the most popular plays of all time, Romeo and Juliet was Shakespeare’s second tragedy (after Titus Andronicus of 1594, a failure). Consequently, the play shows the sometimes artificial lyricism of early comedies such as Love’s Labour’s Lost (pr. c. 1594-1595, pb. 1598) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (pr. c. 1595-1596, pb. 1600), while its character development predicts the direction of the playwright’s artistic maturity. In Shakespeare’s usual fashion, he based his story on sources that were well known in his day: Masuccio Salernitano’s Novellino (1475), William Painter’s The Palace of Pleasure (1566-1567), and, especially, Arthur Brooke’s poetic The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (1562). Shakespeare reduces the time of the action from the months it takes in Brooke’s work to a few compact days.

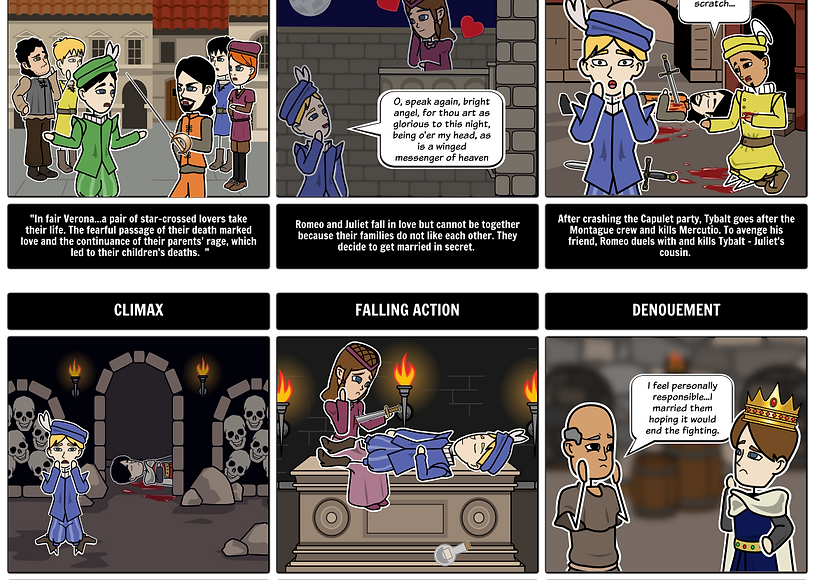

In addition to following the conventional five-part structure of a tragedy, Shakespeare employs his characteristic alternation, from scene to scene, between taking the action forward and retarding it, often with comic relief, to heighten the dramatic impact. Although in many respects the play’s structure recalls that of the genre of the fall of powerful men, its true prototype is tragedy as employed by Geoffrey Chaucer in Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1382)—a fall into unhappiness, on the part of more or less ordinary people, after a fleeting period of happiness. The fall is caused traditionally and in Shakespeare’s play by the workings of fortune. Insofar as Romeo and Juliet is a tragedy, it is a tragedy of fate rather than of a tragic flaw. Although the two lovers have weaknesses, it is not their faults, but their unlucky stars, that destroy them. As the friar comments at the end, “A greater power than we can contradict/ Hath thwarted our intents.”

Shakespeare succeeds in having the thematic structure closely parallel the dramatic form of the play. The principal theme is that of the tension between the two houses, and all the other oppositions of the play derive from that central one. Thus, romance is set against revenge, love against hate, day against night, sex against war, youth against age, and “tears to fire.” Juliet’s soliloquy in act 3, scene 2 makes it clear that it is the strife between her family and Romeo’s that has turned Romeo’s love to death. If, at times, Shakespeare seems to forget the family theme in his lyrical fascination with the lovers, that fact only sets off their suffering all the more poignantly against the background of the senseless and arbitrary strife between the Capulets and Montagues. For the families, after all, the story has a classically comic ending; their feud is buried with the lovers—which seems to be the intention of the fate that compels the action.

The lovers never forget their families; their consciousness of the conflict leads to another central theme in the play, that of identity. Romeo questions his identity to Benvolio early in the play, and Juliet asks him, “Wherefore art thou Romeo?” At her request he offers to change his name and to be defined only as one star-crossed with her. Juliet, too, questions her identity, when she speaks to the nurse after Romeo’s slaying of Tybalt. Romeo later asks the friar to help him locate the lodging of his name so that he may cast it from his “hateful mansion,” bringing a plague upon his own house in an ironic fulfillment of Mercutio’s dying curse. Only when they are in their graves, together, do the two lovers find peace from the persecution of being Capulet and Montague; they are remembered by their first names only, an ironic proof that their story has the beneficial political influence the Prince, who wants the feud to end, wishes.

Likewise, the style of the play alternates between poetic gymnastics and pure and simple lines of deep emotion. The unrhymed iambic pentameter is filled with conceits, puns, and wordplay, presenting both lovers as very well-spoken youngsters. Their verbal wit, in fact, is not Shakespeare’s rhetorical excess but part of their characters. It fortifies the impression the audience has of their spiritual natures, showing their love as an intellectual appreciation of beauty combined with physical passion. Their first dialogue, for example, is a sonnet divided between them. In no other early play is the imagery as lush and complex, making unforgettable the balcony speech in which Romeo describes Juliet as the sun, Juliet’s nightingale-lark speech, her comparison of Romeo to the “day in night,” which Romeo then develops as he observes, at dawn, “more light and light, more dark and dark our woes.”

At the beginning of the play Benvolio describes Romeo as a “love-struck swain” in the typical pastoral fashion. He is, as the cliché has it, in love with love (Rosaline’s name is not even mentioned until much later). He is youthful energy seeking an outlet, sensitive appreciation seeking a beautiful object. Mercutio and the friar comment on his fickleness. The sight of Juliet immediately transforms Romeo’s immature and erotic infatuation to true and constant love. He matures more quickly than anyone around him realizes; only the audience understands the process, since Shakespeare makes Romeo introspective and articulate in his monologues. Even in love, however, Romeo does not reject his former romantic ideals. When Juliet comments, “You kiss by th’ book,” she is being astutely perceptive; Romeo’s death is the death of an idealist, not of a foolhardy youth. He knows what he is doing, his awareness growing from his comment after slaying Tybalt, “O, I am Fortune’s fool.”

Juliet is equally quick-witted and also has early premonitions of their sudden love’s end. She is made uniquely charming by her combination of girlish innocence with a winsome foresight that is “wise” when compared to the superficial feelings expressed by her father, mother, and Count Paris. Juliet, moreover, is realistic as well as romantic. She knows how to exploit her womanly softness, making the audience feel both poignancy and irony when the friar remarks, at her arrival in the wedding chapel, “O, so light a foot/ Will ne’er wear out the everlasting flint!” It takes a strong person to carry out the friar’s stratagem, after all; Juliet succeeds in the ruse partly because everyone else considers her weak in body and in will. She is a subtle actor, telling the audience after dismissing her mother and the nurse, “My dismal scene I needs must act alone.” Her quiet intelligence makes the audience’s tragic pity all the stronger when her “scene” becomes reality.

Shakespeare provides his lovers with effective dramatic foils in the characters of Mercutio, the nurse, and the friar. The play, nevertheless, remains forever that of “Juliet and her Romeo.”